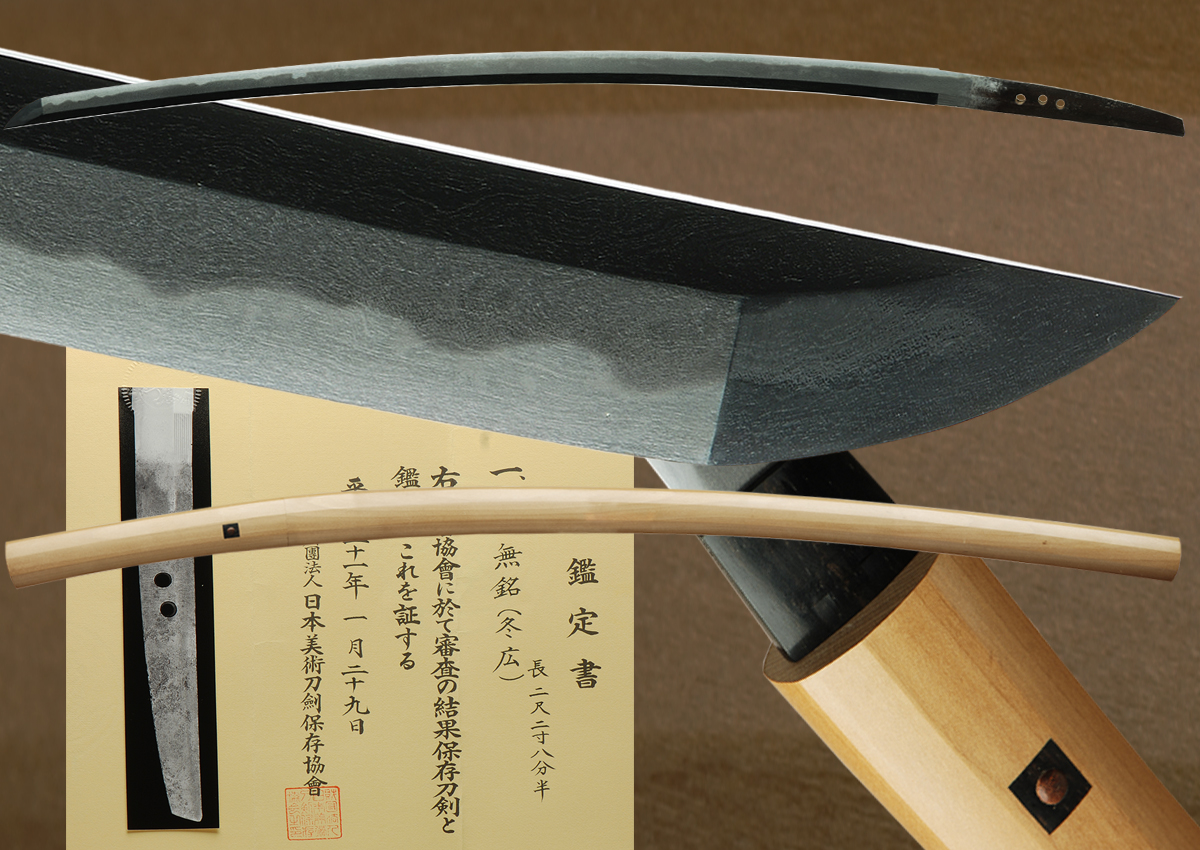

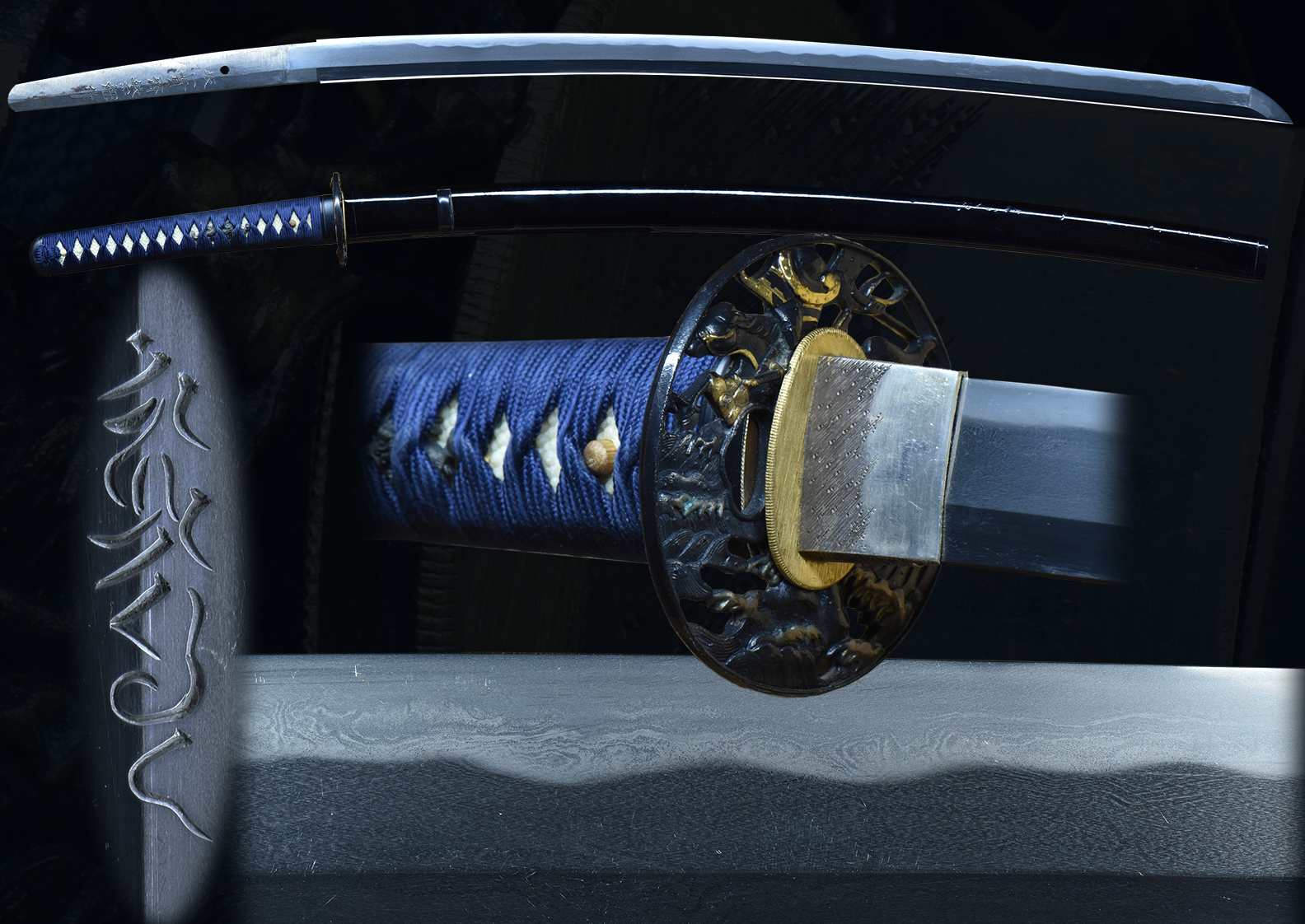

This katana is a beautiful example of a Gassan smith from the muramachi era and was papered to the Tenbun era Gassan school. The Ayasugi hada is brilliant and a standout on this sword which comes fully mounted and adds to the value of this blade.The blade has a silver foil habaki and was just submitted to shinsa and has received a kantei-sho rating from the NTHK (npo) Shinsa team. The hada is a rich looking ayasugi that has some coarseness as in many koto gassan blades. The koshirai has been completely restored and a new saya has been made to store the blade.

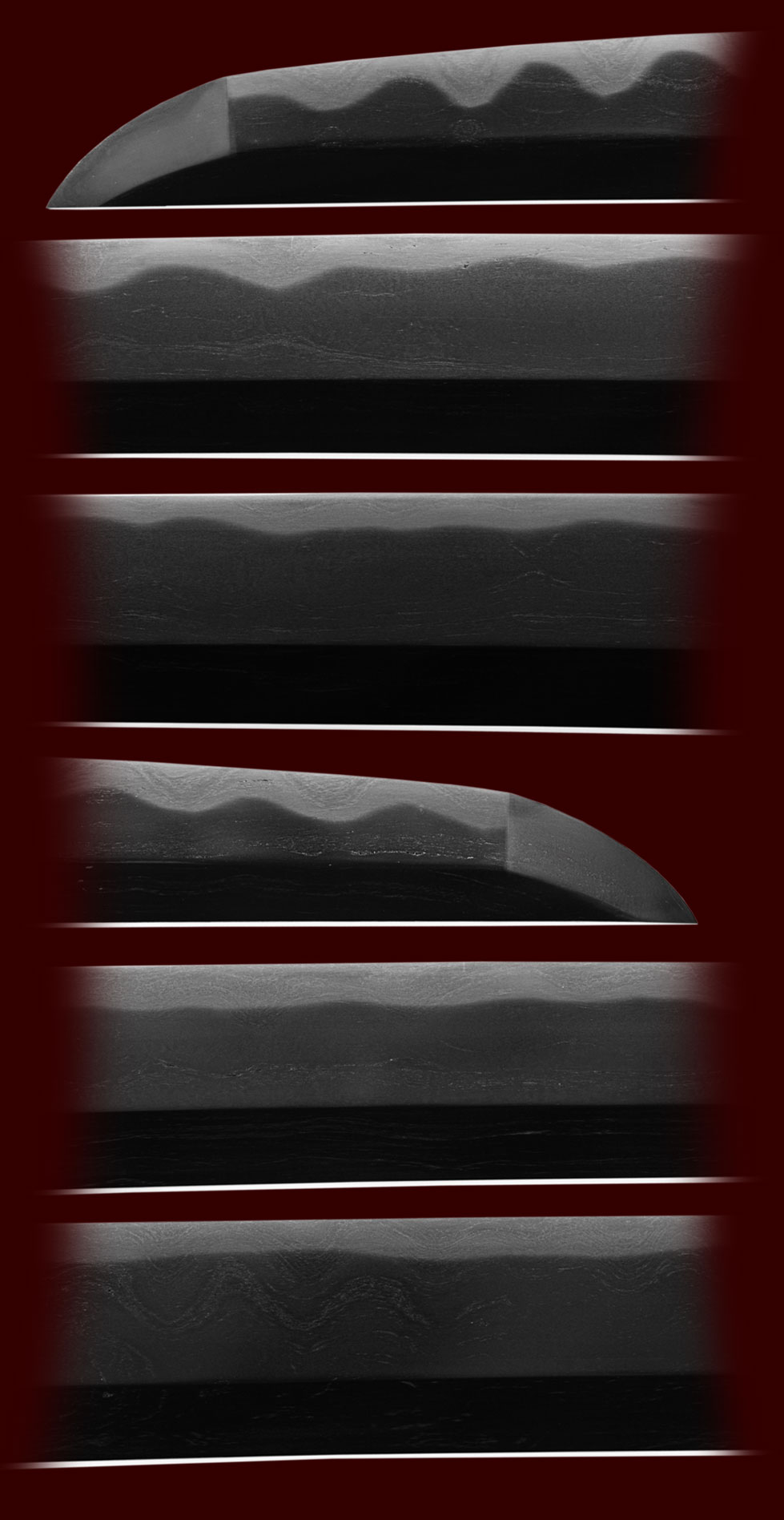

The Gassan school derives, as its name suggests, from Mt. Gassan in the old province of Dewa (present-day Yamagata prefecture), and is characterized by a wavy grain called ayasugi hada. According to tradition, it was founded by a smith named Kiomaru (or Kishin Dayu, as he was also known), who lived in the sacred grounds of Mt. Gassan back in the 12th century. Ever since, swordsmiths have flourished at the foot of Mt. Gassan, and a number of masters have appeared, in a long succession. From the Kamakura period through the Muromachi period, swords inscribed with the Gassan signature were famous all over the country for their practical usefulness and the beauty of their ayasugi hada, but when the Warring States period ended at the end of the 16th century, the number of blacksmiths dwindled. From the start, Mt. Gassan was a site of mountain worship, and the blacksmiths who lived there were peculiar people who secluded themselves among the mountains to purify themselves before forging swords. They were ascetics, similar to Shugendo practitioners. Gassan was the name of the object of worship, and inscribing such a name on a sword would normally be inexcusable. Probably Gassan swords were originally intended for funeral rites, rather than as weapons. They were not meant for killing people, but were associated with the faith, I believe. The Gassan school’s ayasugi hada layer appeared when steel with different carbon contents were mixed and combined at a certain point, but the formula was kept secret.

At the end of the Edo period, Gassan Sadayoshi, who was the successor to the Gassan smiths, moved to Osaka. I believe he wanted to show the world the Gassan spirit one more time.

The Gassan school origins remains to this day one of the most prestigious and successful lines of sword forging. The roots of Gassan extend far back into the Kamakura period (1185-1333 AD), and it is suspected perhaps even as early as Heian period (794-1185 AD). The home of Gassan was in Dewa province in the northern region of Honshu where they were the only indigenous school to Dewa. The name “Gassan” actually refers to one of three sacred mountains of Dewa, or “Dewa Sanzan”, the other two being Mt. Haguro and Mt. Yudono. It is a very mountainous and remote region, and was even more so in the earliest days of the school. From the very earliest works of the Gassan school, they exhibit a type of hada called “Ayasugi” which is comprised of long evenly undulating stacked wave pattern. Interestingly enough this pattern of the same name is carved in the interior walls of the body of the Shamisen (a guitar like musical instrument) to improve the tone. This pattern eventually became the hallmark of Gassan works and is often referred to as “Gassan Hada” as it continued to be refined and perfected by the Gassan smiths up until the current Gassan head and Living National Treasure smith, Gassan Sadatoshi. The Gassan school faded from view around the beginning of the 17th century, and then was revived with Gassan Sadayoshi who was born in 1780. Sadayoshi traveled from Dewa to the forge of Suishinshi Masahide, who was striving to rediscover the techniques of Koto masters. Masahide was a proliferate teacher, and is said to have had over 200 students. Sadayoshi became one such student and later settled in Osaka to open his own forge. The line was re-established with him and his adopted son, Gassan Sadakazu became the heir to the line entering very difficult times for swordsmiths; the Meiji Restoration. The Samurai class was effectively abolished and swords were no longer a weapon that could either be worn, nor were they in much demand as Japan Westernized, so swordsmiths were relegated to finding work in other trades. Many turned to tool making, blacksmithing, or other related trades. However Gassan Sadakazu contined on with sword making and found a market making copies of famous swords for influential and affluent clientele, as he was quite gifted in making swords in the Bizen, Soshu, and Yamato traditions. He became a Teishitsu Gigeiin or “Artist under the Imperial Household” and thus was called upon by the Imperial Family to make swords that would be worn, or bestowed as gifts by the Imperial Family. He survived the times and his son, Gassan Sadakatsu, would become the luminary smith of the 20th century, and also receive the dedicated patronage of the Imperial Family.

If you take a look at the blade first of all the forging structure catches the eye. It appears as continuous waves from the base to the tip whereas the valleys show some mokume areas. The jihada stands out and the steel is blackish. So all in all we have the typical characteristics of the Gassan school and an ayasugi-hada is therefore also called Gassan–hada. The hamon bases on gunome/notare/sugu-ha midare but the waves of the jihada force it into a notare-like appearance. The nioiguchi is subdued and the entire jiba lacks clarity and brightness. Thus this is a typically rustic work of that school and all and all typical Gassan.The koshirae is en suite and of dragon motif. There is a deep rich brown sageo and tsuka-ito to match. The rayskin ( same ) is black as well as the lacquer finish of the saya.

Japanese dragons and the koshirai (日本の竜 Nihon no ryū) are diverse legendary creatures in Japanese mythology and folklore. Japanese dragon myths amalgamate native legends with imported stories about dragons from China, Korea and India. The style of the dragon was heavily influenced by the Chinese dragon. Like these other Asian dragons, most Japanese ones are water deities associated with rainfall and bodies of water, and are typically depicted as large, wingless, serpentine creatures with clawed feet. The modern Japanese language has numerous “dragon” words, including indigenous tatsu from Old Japanese ta-tu, Sino-Japanese ryū or ryō 竜 from Chinese lóng 龍, nāga ナーガ from Sanskrit nāga, and doragon ドラゴン from English “dragon” (the latter being used almost exclusively to refer to the European dragon and derived fictional creatures).

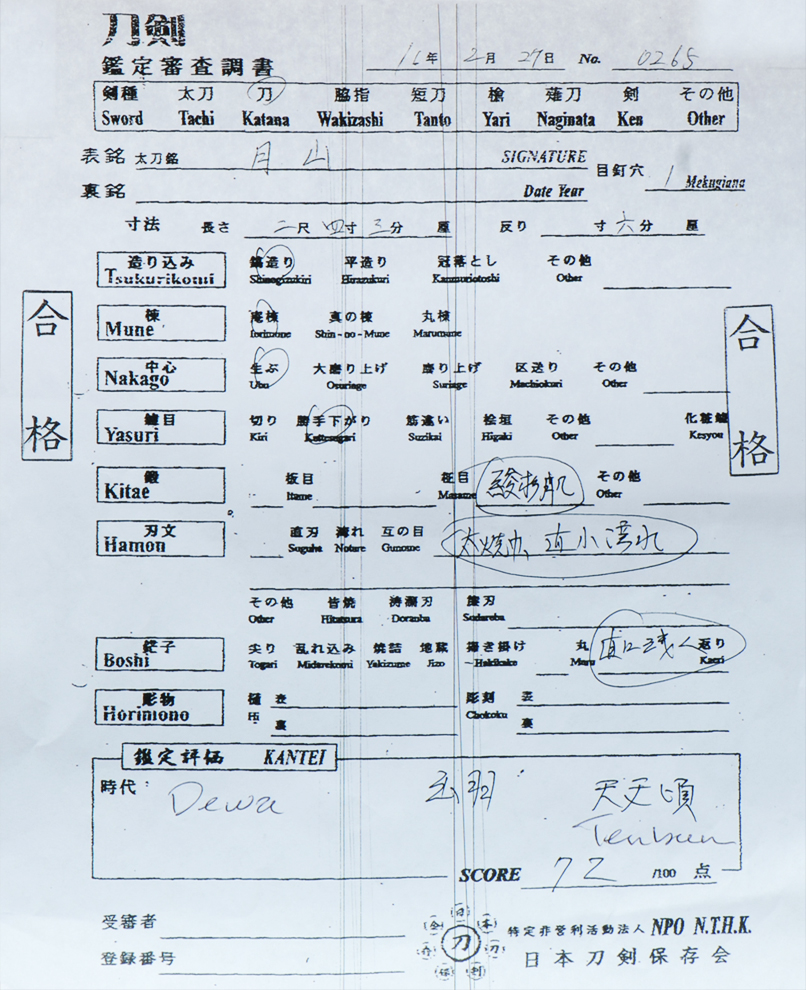

- Mei: Gassan

- Date: Koto (Tenbun) 1400’s

- Nagasa: 29″ inches

- Sori: 16.5 mm

- Width at the ha-machi: 31.6 mm

- Width at the yokote: 16.5 mm

- Thickness at the mune-machi: 6.7 mm

- Construction: Shinogi zukuri

- Mune: Iori

- Nakago: Ubu

- Kitae: Itame/mokume

- Hamon: Midare Gunome

- Boshi: Maru

- Condition: Good polish

Email us if your interested in this item and remember to include the order number for this item: fss-693.

This is the work sheet from the shinsa. When the papers are received they will be forwarder to the new owner.

For Sale