Description:

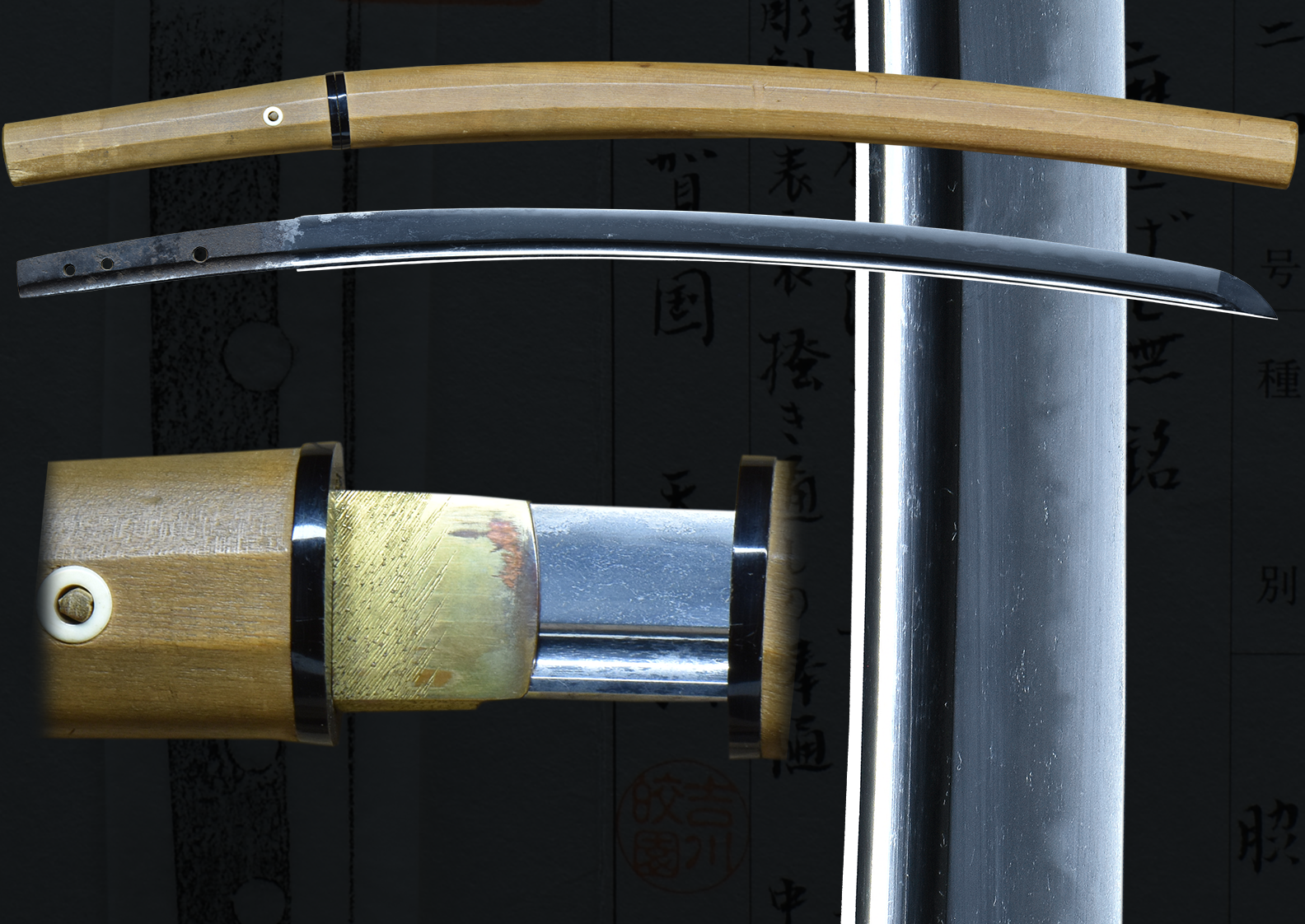

This is a beautifully constructed katana attributed to the Mizuta Den from Bichu provence in beautiful mounts. It is a signed han-dachi style of mountings. This fine sword was made in the 1600’s. The koshirae is very exquisite but of a true refined samurai style. They are plush looking without being too flashy in appearance. The blade is very well forged and the hada/grain texture is smooth looking and dark. There is mokume and itame both. The hamon is very active and has abundant hataraki/activaty. It is nioi based, nie mix with many sunagashi etc. visible. The shape is very nice with a well balanced curvature and o-suriage. This sword is a very fine blade and has been submitted for shinsa/appraisal to Yoshikawa Sensei.

The blade itself is a notare, peppered with ara-nie and small activities throughout emulating the great old blades of past. The hada is so fine and well worked of ko-itame with mokume. It is covered in ji-nie and has an oily appearance that is found in the best of blades. A rare package!! At 23 7/8” it was most probably used as an uchigatana.

During the twelfth century Uchigatana started to be used and by the Muromachi Period approximately 1336 to 1573 the uchigatana began to rival the tachi as the sword of choice by warriors. Unlike the tachi, the uchigatana was worn edge-up in the belt, this and usually being slightly smaller than the tachi was the main difference between the tachi and the uchigatana. Since it is worn differently, the engraved words on the sword are also opposite to the tachi, making the words still upright instead of upside-down like when one wears the tachi like an uchigatana. This sword became popular for several reasons, the uchigatana was more convenient to wear and did not get in the way of using a polearm as much as a tachi, also the frequency of battles fought on foot and the need for speed on the battlefield, were major reasons for the uchigatana being rapidly accepted and indicated that battlefield combat had grown in intensity. Since it was shorter, it could be used in more confined quarters, such as inside a building.

Unlike the tachi, with which the acts of drawing and striking with the sword were two separate actions, unsheathing the uchigatana and cutting the enemy down with it became one smooth, lightning-fast action (this technique was called battojutsu otherwise known as Battokiri). The curvature on the blade of the uchigatana differs from the tachi in that the blade has curvature near the sword’s point (sakizori), as opposed to curvature near the sword’s hilt (koshizori) like the tachi. Because the sword is being drawn from below, the act of unsheathing became the act of striking. For a soldier on horseback, the sakizori curve of the uchigatana was essential in such a blade, since it allows the sword to come out of the saya (sheath) at the most convenient angle for executing an immediate cut.

The word uchigatana can be found in literary works as early as the Kamakura Period, but during that time the uchigatana was used only by individuals of low status and privates in the ranks. Most uchigatana made during the early Kamakura Period were not of the highest standard, and because they were considered disposable, virtually no examples from these early times exist today. It wasn’t until the Muromachi Period (considered by some to be a kind of Dark Age in the history of the Japanese Sword), when the samurai began to use them to supplement the longer tachi, that uchigatana of high quality began to be made. In the Momoyama and Edo Periods, the tachi was almost totally abandoned and the custom of wearing a pair of long and short uchigatana together, the daisho (literally “big-little”) became the dominant sign of the Samurai class.

The tsuba depicts bamboo grasses and trees and also a paulownia leafed tree in cartouche like settings. An uncommon and exceptional depiction framed within the tsuba of iron and gold with a mottled texture of a blackish lacquer is found on this koshirae. The overall appearance is exceptional and rarely in as good as a condition as this. Tree like settings in Japanese art follows many traditions. There is a silver ribbed habaki.

This blade is in original polish that has some minor scuffing only. If polished again in the future it would be an even more stunning blade, showing extremely fine detail in the workmanship .As can be seen there is a small scuff in the boshi that would disappear with polish.

mei on the fuchi. It reads: “Tôyô’an Katsuô hour” (東陽菴勝應彫) – “carved by Tôyô’an Katsuô”

Haynes lists one Katsuô, H 02861.0, stating that he worked around 1800, made tsuba, and that his kaô is unrecorded. So not sure if its this artist, but possible. Also the gô “Tôyô’an” is unrecorded what would make this fuchi actually an important reference for this artist as it tells us the pseudonym he used. These handachi mounts are all matching and signed. An important fact to understand on original antique mounts.

The handachi fittings are richly engraved in arabesque with blue sageo and black tsuka ito. The menuki are of a Vajra and Ken. The fittings appear to be silver washed over copper. A beautiful package!

- Mei: Unsigned attributed to Mizuta, Bitchu Provence

- Date: Kanbun (1661-1673)

- Nagasa: 23 7/8 inches

- Sori: 12.0 mm

- Width at the ha-machi: 29.0 mm

- Width at the yokote: 20.4 mm

- Thickness at the mune-machi: 7.7 mm

- Construction: shinogi-zukuri

- Mune: iori

- Nakago: suriage

- Kitae: ko-itame

- Hamon: notare

- Boshi: hakikakeru

- Condition: good older polish

Email us if your interested in this item and remember to include the order number for this item: fss-684.

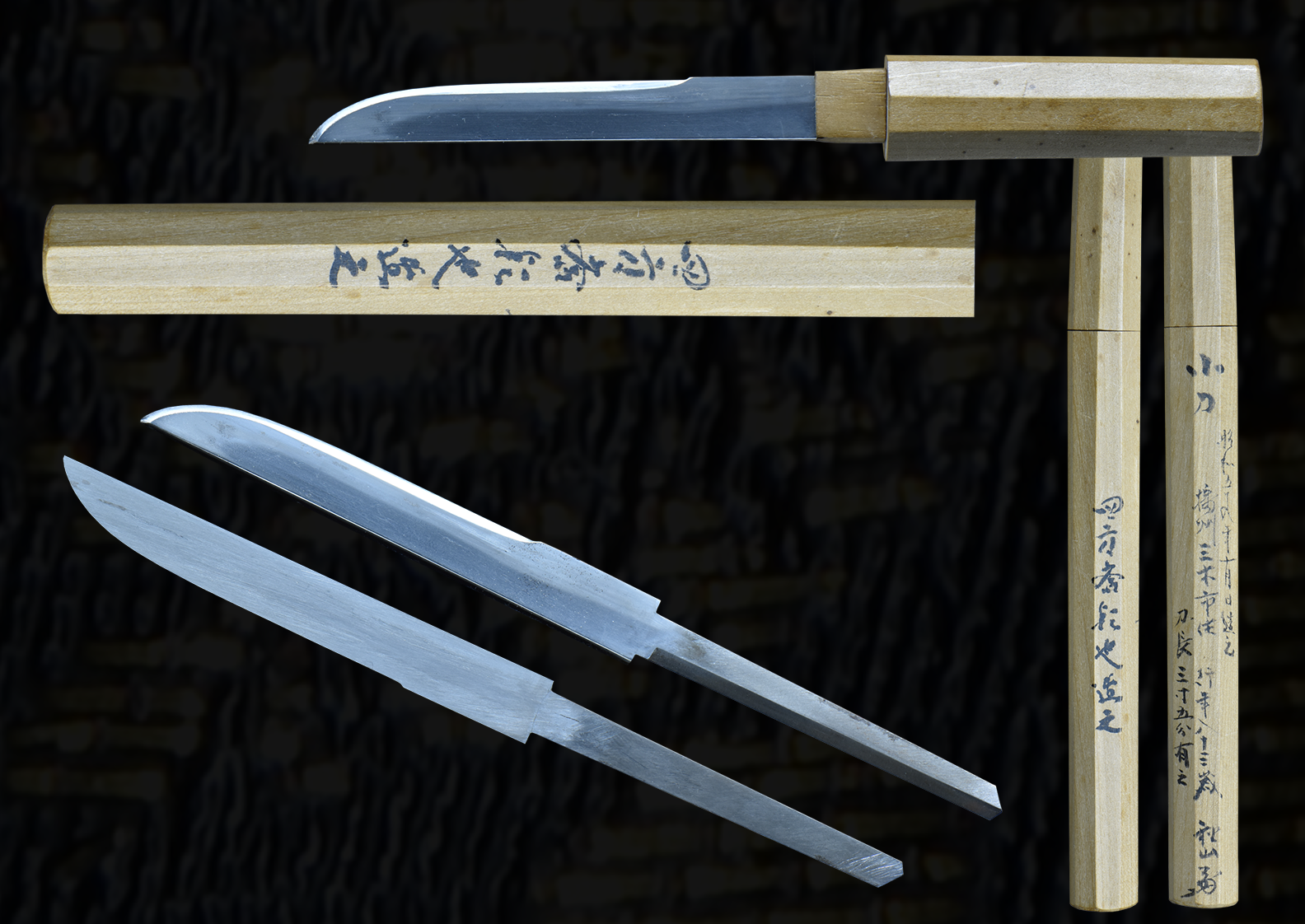

NTHK KANTEI-SHO CERTIFICATE

Click to Enlarge Image

Translation of the certificate:

kantei-sho (鑑定書) – Certificate Den Mizuta (伝水田)

shôshin (正真) – Authentic

nagasa 2 shaku kore ari (長さ貮尺有之) – Blade length 60.6 cm

Shôwa gojûyonnen gogatsu nijûshichinichi (昭和五十四年五月二十七日) –

May 27th 1979 Nihon Tôken Hozon Kai (日本刀剣保存会) – NTHK

No 4680

meibun (銘文) – Signature: suriage mumei (磨上げ無銘)

kitae (鍛) – Foging: ko-itame (小板目)

hamon (刃紋) – Hardening: notare (のたれ)

bôshi (鋩子) – Hardening in tip: nie te hakikakeru (沸えて掃ける), showing nie and hakikake

chôkoku (彫刻) – Engravings:

nakago (中心) – Tang:

mekugi-ana (目釘穴) 1 (壱個),

yasurime (鑢): kiri (きり)

bikô (備考) – Remarks: Kanbun-goro Bitchû (寛文ごろ備中), around Kanbun (1661-1673),

Bitchû shinsa’in natsu’in (審査員捺印) – Seals of Judges: 4 seals

General info on the Mizuta School:

The Ko-Mizuta school was a late Muromachi-period successor of the Aoe school. On the basis of place names in signatures we know about the various production sites of this school, that is to say Ebara (荏原), Ihara (井原), Azae (呰部, also read Asaibe), Matsuyama (松山), and Niimi (新見). The kotō-era Mizuta smiths are referred to as “Ko-Mizuta” or “Matsuyama-Mizuta” and did not sign with “Mizuta.” This name goes back to the shintō-era successor Ōyogo Kunishige (大与五国重) who had moved to Mizuta. Even if the roots of the Mizuta school were in the Aoe school, their stylistic origins have to be found in the Tatsubō school of Bingo province as their workmanship was continued by the Ko-Mizuta smiths and appears as a nie-laden gunome-midare, a midare-bōshi with a relative long kaeri, and a ha-agari kurijiri as tip of the tang. The later Kunishige smiths applied a gunome-based ō-midare, an ō-notare, or in case of tantō also a hitatsura. The tang is rather long and resembles the ha-agari kurijiri tangs of the Sue-Bizen school. That means the Ko-Mizuta school demonstrates a style somewhere between Tatsubō and Sue-Bizen and sometimes it is hard to distinguish between works of these three schools.

Bitchû-based Mizuta smiths working around Kanbun:

KUNISHIGE (国重), 6th gen., Kanbun (寛文, 1661-1673), Bitchū – “Bitchū Mizuta-jū Ōtsuki Katsubei Kunishige” (備中国水田住大月勝兵衛国重), real name Ōtsuki Katsubei (大月勝兵衛), he also bore the first name Shōbei (庄兵衛), son-in-law of Ichizō Kunishige, some sources list him as son of the 5th gen., he signed first with Kuniharu (国春) and lived in Bitchū ́s Inoo (井ノ尾), he was granted with the honorary title Kawachi no Daijō (河内大掾) and died in the twelfth month of Jōkyō four (貞享, 1687), ō-gunome-midare with rough nie in ji and ha, wazamono, chūjō-saku KUNISHIGE (国重), Meireki (明暦, 1655-1658), Bitchū – “Bitchū no Kuni Mizuta-jū Sabei Kunishige” (備中国水田 住左兵衛国重), “Bitchū no Kuni Mizuta-jū Kunishige” (備中国水田住国重), first name Sabei (左兵衛), student of the 4th gen. Kunishige (Saburōbei), chūjō-saku

KUNISHIGE (国重), Manji (万治, 1658-1661), Bitchū – “Bitchū no Kuni Ōtsuki Shinjūrō Kunishige” (備中国大月 新重郎国重), real name Ōtsuki Shinjūrō (大月新重郎), student of the 4th gen. Kunishige (Saburōbei), he moved later to Awa province

KUNISHIGE (国重), Kanbun (寛文, 1661-1673), Bitchū – “Bitchū no Kuni Mizuta-jū Kunishige” (備中国水田住 国重), real name Ōtsuki Zen ́emon (大月善右衛門), he is listed as student of Hachirōzaemon Kunishige (八郎左衛門 国重) but this Kunishige is dated to the Shōtoku era (正徳, 1711-1716), he moved later to Takamatsu (高松) KUNISHIGE (国重), Kanbun (寛文, 1661-1673), Bitchū – “Bitchū no Kuni Mizuta-jū Mo ́emon no Jō Kunishige” (備中国水田住茂右衛門国重), “Bizen Okayama-jū Kunishige” (備前岡山住国重), real name Ōtsuki Mo ́emon (大月右衛門), he is listed as student of Hachirōzaemon Kunishige (八郎左衛門国重) but this Kunishige is dated to the Shōtoku era (正徳, 1711-1716), chūjō-saku

KUNISHIGE (国重), Enpō (延宝, 1673-1681), Bitchū – “Bitchū no Kuni Mizuta-jū Ōtsuki Yogo ́emon Kunishige” (備中国水田住大月与五右衛門国重), real name Ōtsuki Yogo ́emon (大月与五右衛門), he also worked in Bingo and Awa, chūjō-saku

For Sale